The United States and Canada began negotiations in 1920 to identify responsibilities and alternatives for a highway that would provide a land route into the US territory of Alaska. At that time, Alaska was largely wilderness populated by Alaska Natives, trappers, and miners. Getting to Alaska from the US was primarily by sea and air; there was no direct road. Roads that existed were unpaved and mostly mud.

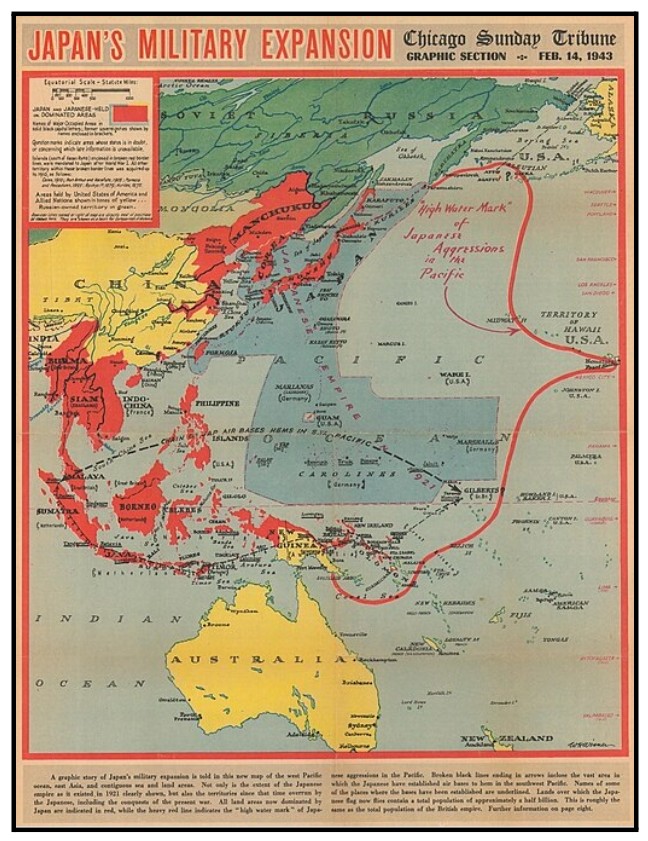

On December 7, 1941, the Japanese Army bombed Pearl Harbor in the US territory of Hawaii, propelling the US into World War II. Despite the surprise attack, the US was aware of the Japanese threat; in June 1940, the US Army had ordered 5,000 troops to Alaska.

With the entry of the US into World War II, building the Alaska Highway became a matter of urgency for national security. The US needed an overland connection to Alaska to move troops and supplies; shipping routes were vulnerable to attack. In addition to the direct attack on Hawaii, the Japanese dominated the Pacific and, by 1942, the Japanese Empire stretched all the way up into the Aleutian Islands. The Axis threat to North America stretched all along the Pacific coast.

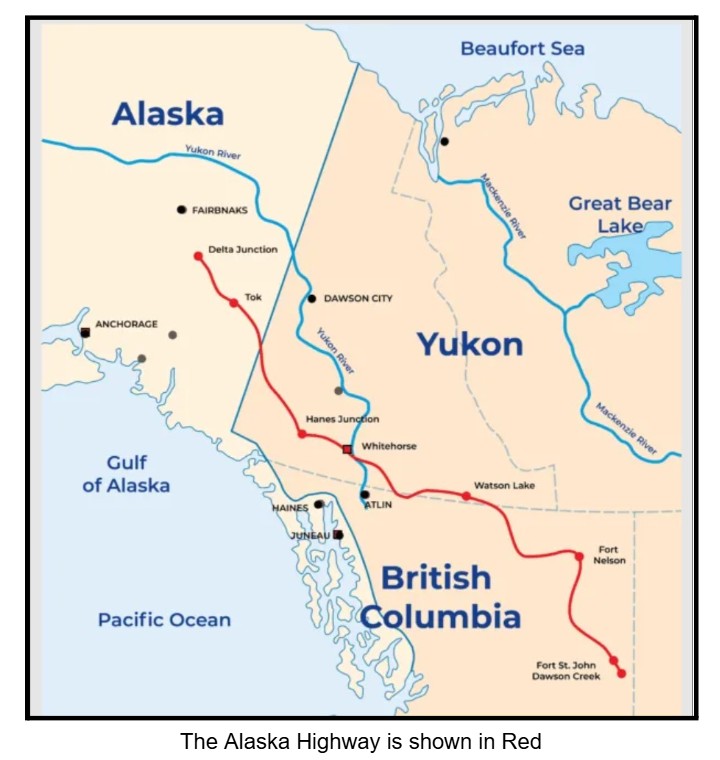

Canada and the US came to an agreement; the US paid for the construction and the Alaska Highway took an inland route across Canada, starting from Dawson’s Creek, British Columbia. This route was considered less vulnerable than alternatives closer to the coast. The US engaged an army of 26,000 engineers, lumbermen, and road construction workers to plot, clear the way, and construct the road. The project was approved and construction began in March 1942.

The massive endeavor took on an even greater sense of urgency after the Japanese armed forces invaded a US Navy weather station on Kiska in the far east end of the Aleutian Islands. Kiska was occupied by the Japanese Empire between 6 June 1942 and 28 July 1943.

The Alaska Highway, unpaved and primitive, was formally opened to military traffic on 20 November 1942. Work continued throughout the war years to widen the road, improve surfaces, build bridges, and straighten curves. While the road remained challenging and without services in many areas, the Alaska Highway (sometimes referred to the Alcan Highway) was opened to civilians in 1946.

The Alaska Highway and Victor “Vic” Wenger

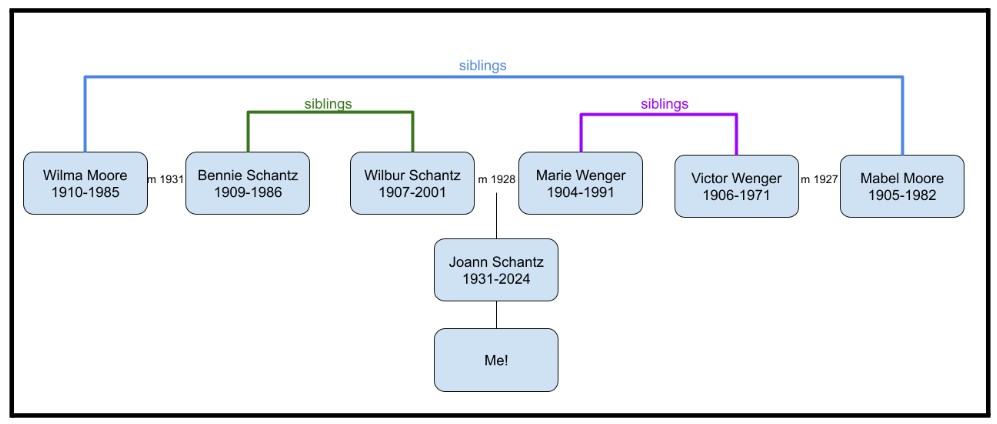

Vic was my granduncle, the younger brother of my grandmother, Marie (Wenger) Schantz (1904-1991). He was born on the family farm in Noble township, Washington, Iowa on 7 July 1906. The children in the family attended country schools in Washington and Henry counties until they moved on to high school “in town” at Washington High School. Vic graduated in May 1924. After graduation, he went to the Coyne Electrical School in Chicago for advanced training.

Mabel Moore became his bride on 23 March 1927. Mabel was a 1923 graduate of Washington High School; they had attended school together. The couple was married at the First Christian Church parsonage in Washington where my grandmother, Marie, and Stanley Moore, Mabel’s brother, acted as witnesses and stood up with the couple. Vic and Mabel initially lived on a farm in Henry County, just south of Washington County while Vic worked for the Iowa Southern Utilities company. The family soon moved into town where Vic was employed as a mechanic and blacksmith.

On 1 October 1928, Vic and Mabel became the parents of a son, Jesse Moore Wenger. Their daughter, Phyllis Ann Wenger, was born on 21 January 1935. The family moved to Mason City, Iowa in 1941 for a few years and then to Clear Lake, just west of Mason City. Vic was not high on the draft list for World War II. He was already a 34-year-old married man with two children at the time of registration for the draft. Vic served the war effort and his country’s safety in a different way.

In April 1943, Vic became one of a crew of twenty from the E.M. Duesenberg company in Clear Lake, Iowa to leave for the 1943 season of work on the Alaska Highway. The crew first arrived in Edmonton, Alberta, Canada to support this tremendous effort. Vic served as a mechanic for the team. Work after 1942 focused on transforming the primitive road into a permanent all-weather gravel road.

Conditions for the workers were rugged and challenging. The men endured swamps, torrential rains, mud, sludge, and drudge during the summer months of “good construction weather.” Workers lived in tents and constantly battled flies and mosquitos.

The Alaska Highway was approximately 1,700 miles long at the opening in 1942. Work continued on throughout the decades following the official opening. After decades of straightening, bridge building, and smoothing, the road was 1,387 miles as of 2012. It’s fully paved. Take a road trip!

The Wenger Family After World War II

Vic returned to Iowa after the 1943 work season. Tragedy struck in 1956 when their son Jesse, living and working as an engineer in Chicago, was in an auto accident that left him paralyzed with a “slow recovery.” Wilbur, Marie, and Leonard Schantz drove to Tennessee to visit him at the Kennedy Veterans Hospital. Jesse never recovered. He died in the hospital in 1960.

Vic, Mabel, and Phyllis moved to Mankato, Minnesota and then on to Rapid City, South Dakota in 1962 where Vic passed away on 19 February 1971. After his death, Mabel and Phyllis moved back to Washington, Iowa to be near their extended family. Phyllis had intellectual disabilities and lived with her mother for most of her life. Phyllis worked at the Washington County Development Center and participated in Special Olympics bowling tournaments. Mabel passed away in 1982 and Phyllis in 2021. Vic, Mabel, Jesse, and Phyllis were all laid to rest at Elm Grove Cemetery in Washington, Iowa.

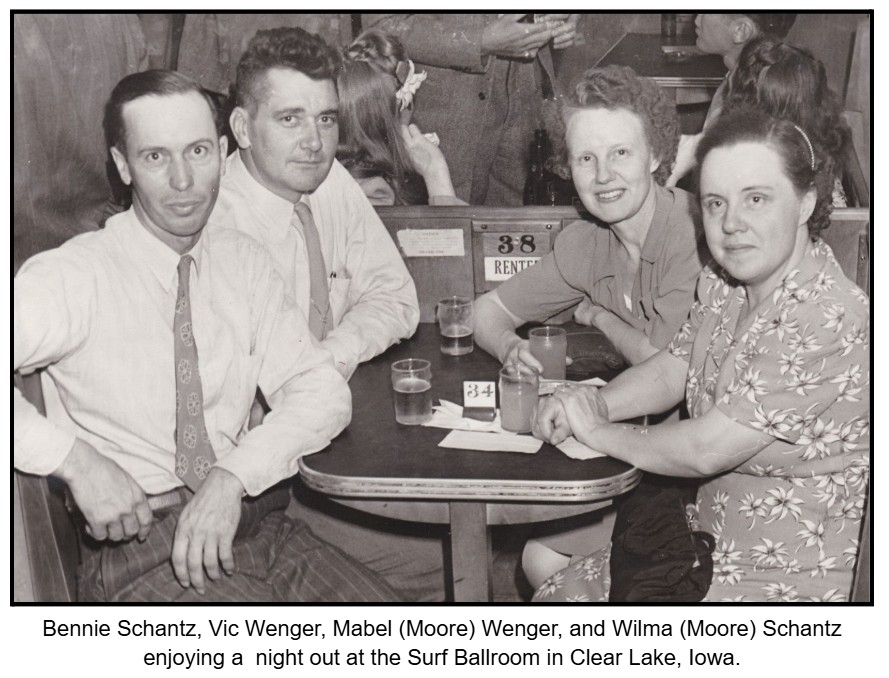

We have a unique double connection with Vic and Mabel. Vic was Marie’s brother. Mabel’s sister, Wilma Moore, married Wilbur Schantz’s brother Bennie Schantz.

The construction of the Alaska Canada Highway ranks as a marvel of the twentieth century in terms of the amount of effort deployed, how quickly the road was created, and the clearing, bridges, and engineering involved. Vic Wenger was on the ground as a part of this historic project. Both military and civilian teams responded to the challenges faced in its construction. The legacy of the highway is still felt in the region and also enjoyed by tourists. Knowing about his participation brings us closer to these events of the war years. Vic Wenger was a part of a historic project. You can think of Vic while driving to Alaska on the highway today.

If you would like more information or need detail about my sources, please contact me at reneecue@gmail.com.

If you would like to learn more about the construction of the Alaska Highway, watch “Modern Marvel: The Alcan Highway”